Anti-poaching (AP) teams are hired and funded under Save Vietnam's Wildlife, and approved by protected area managers where they sign a joint contract between the two. They undergo approximately one month of training in Vietnamese forestry law, species identification, self-defense, field training, first aid, and using SMART.

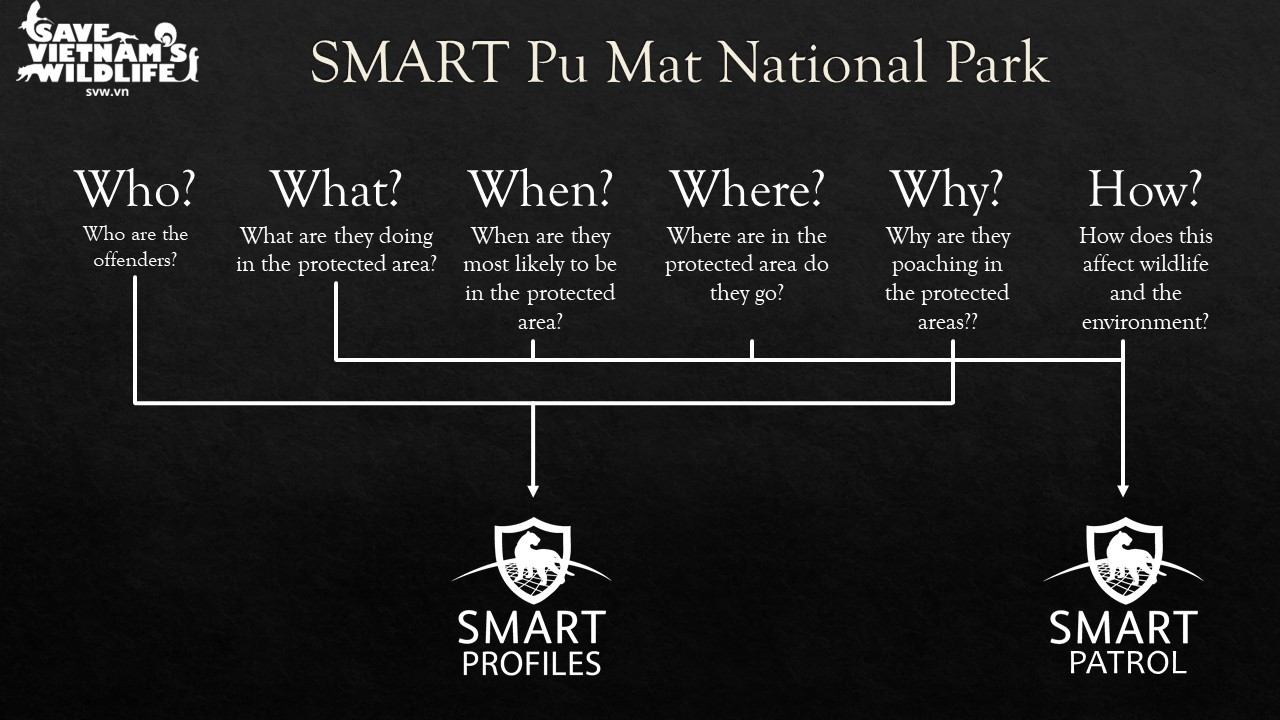

AP patrols stay with forest rangers for 15-20 days of patrolling at various ranger stations each month, and an assigned Data Manager typically processes, cleans, analyzes and reports SMART data for all patrols to the park director and SVW coordinators. At the beginning of each month, a SMART report is generated by the data manager; based on the intelligence from this report, a patrol plan will be discussed with the ranger and anti-poaching members, and then submitted to the protected area director for approval; mobile units are on standby and led by forest rangers to rapidly respond to any emergencies, locations outside of planned patrol areas, or situations accessible by road.

Rangers were trained to use SMART mobile through vertical knowledge transfer in the field, and by the end of 2020, 100% of the forest rangers (73 people) were all effectively using SMART, increasing patrol data coverage across the entire protected area (Figure 1).