Enhancing the biodiversity impact of local budgets in Mongolia: implementation of the Law on Natural Resource Use Fees

In Mongolia, 77% of the soil is degraded due to activities such as agricultural expansion and mining, while poaching has threatened the snow leopard and other native animals. Insufficient spending on biodiversity largely contributed to this. Although the 2012 Natural Resource Use Fees Law (NRUF) states that a minimum share of the revenues from fees for using natural resources must be spent on conservation and restoration, the law was not effectively implemented by local governments. In 2021, Mongolia only spent 0.2% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on biodiversity.

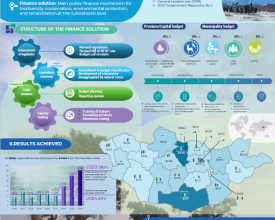

Amid this scenario, BIOFIN supported Mongolia in strengthening the implementation of the NRUF. This process included 1) analyzing existing regulations and drafting new ones; 2) creating a public database to track environmental expenditures; and 3) building capacity and raising awareness.

As a result, Mongolia spent USD 13.98 million on biodiversity in 2024, an increase of 225% compared to 2021, and more than doubling the projected USD 5-6 million per year.

Context

Challenges addressed

The expansion of harmful activities has threatened biodiversity conservation in Mongolia. 77% of the country’s soil is degraded due to agricultural expansion, mining, infrastructure development, and climate change. Poaching has also pressured species such as the marmot and snow leopard, listed as endangered and vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Mongolia’s low biodiversity expenditure — 0.2% of its GDP, or USD 4.29 million in 2021— worsened this scenario. The NRUF law requires that a minimum share of revenues from natural resource use fees is spent in conservation and restoration. Yet under the 2011 Integrated Budget Law, these revenues go to local governments, which must then allocate these funds to biodiversity when defining their budgets. This context of fiscal decentralization, coupled with limited cooperation across levels of government and inconsistent regulations hindered NRUF's full implementation, making biodiversity expenditure below ideal.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

These interconnected building blocks are mutually reinforcing and essential for the aggregate success of the solution. While improved communication and cooperation between government agencies through call circulars and the revision and approval of environmental budgets is critical, local decision-makers must first possess the necessary knowledge and skills to design their budgets and incorporate the instructions from call circulars.

Nationwide capacity-building and awareness-raising efforts further enhance the effectiveness of inter-agency cooperation and ensure that knowledge is transferred through these interactions.

Lastly, the contribution of the database to accountability and transparency is maximized with local actors’ adherence and accurate provision of information, which is reinforced through trainings, workshops, and awareness-raising meetings.

Building Blocks

Enhancing regulation and strengthening cooperation across government levels for effective law enforcement

BIOFIN and the National Audit Office of Mongolia jointly assessed the implementation level of the NRUF and examined institutional and regulatory gaps affecting law enforcement. The review found that weak enforcement resulted from legal ambiguities, inconsistent regulations, and ineffective coordination among government agencies. Following this process, BIOFIN provided technical assistance to develop revised regulations that address these legal ambiguities.

Beyond regulatory enhancements, a fundamental component was strengthening cooperation and communication between government agencies — ensuring that the NRUF and its revised regulations are understood and effectively implemented. This is particularly important since local governments are responsible for incorporating the NRUF, a national law, into their budget processes. To support this, the Ministry of Finance (MoF) began to issue bi-annual budget call circulars: official instructions that explain the procedures to prepare next fiscal year’s budget, helping local governments to incorporate biodiversity expenditures. The MoF also increased efforts to review and approve dedicated budgets for environmental protection and natural resource rehabilitation.

Enabling factors

Enabling factors include mutual understanding among government agencies of the interconnectedness of biodiversity finance procedures and a willingness to cooperate. Support from biodiversity finance specialists, particularly the BIOFIN team, was also critical in identifying gaps in regulations and coordination, and in effectively supporting the development of solutions to address them.

Lesson learned

A key lesson learned from this building block is that cooperation and communication can bridge the gap between biodiversity finance law and practice, in combination with clear regulations that support enforcement. Although the NRUF was approved in 2012, these inconsistencies have prevented the law from achieving its intended outcomes.

While the NRUF is specific to Mongolia, the replicability of this building block goes beyond that. It consists of the fact that biodiversity finance is an inherently interconnected matter, and government solutions typically involve multiple agencies at different levels, from finance departments to environmental sectors. This building block shows that other governments-national, regional, or local — seeking to strengthen biodiversity finance through laws and regulations must give equal attention to governance structures, cooperation mechanisms, and regular communication and guideline tools, such as the bi-annual call circulars.

Resources

Developing a public database to track biodiversity finance, improve accountability, and ensure that governments’ expenditure responsibilities are met

A public Environmental Budget and Expenditure database was developed to disclose environmental budgets and expenditures (since 2023). Its intuitive and visual layout allows users to track how much each province has spent on biodiversity each year. This has two main implications.

First, by having to thoroughly fill the database, local governments can use it as a tool to better understand how to develop their own environmental budgets and clarifying which categories should be included.

Second, the public database promotes accountability and transparency in environmental planning and budgeting, encouraging governments to fulfill their biodiversity finance responsibilities under the NRUF and, ultimately, functioning as an effective monitoring tool.

Enabling factors

Technical capacity and funding for the development, implementation, and maintenance of the database; local governments’ understanding of the database and commitment to disclose their environmental budgets and expenditures.

Lesson learned

Beyond legal responsibilities, monitoring and accountability tools (such as publicly available databases) can create additional incentives for enforcing biodiversity expenditure laws. These tools offer a practical way to translate disaggregated information into an easily accessible format for tracking biodiversity finance. It is important, however, that the development of these tools is accompanied by efforts to raise awareness of their existence, ensuring they are effectively used to monitor progress and support law enforcement.

Resources

Nationwide capacity-building and awareness-raising for environmental budgets’ planning, implementation, monitoring, and reporting

Lastly, this solution has included capacity-building activities and awareness-raising meetings across all 21 provinces and the capital since 2022. For capacity-building, trainings have been provided online and in-person, while forums and workshops were also organized for broader discussions. Awareness-raising meetings have targeted specific local decision-makers and have been conducted in-person.

The objective of these activities is to equip local actors with the knowledge and skills needed for environmental management and budgeting aligned with the NRUF, through exercises on planning, execution reporting, and monitoring and evaluation of local environmental budgets. Trainings have also focused on the Environmental Budget and Expenditure Database, helping local governments to disclose their information and improving data-driven planning and decision-making.

Moreover, UNDP BIOFIN is working with the government of Mongolia in the development of an expenditure taxonomy, which will provide a standardized categorization of environmental expenditures, adding clarity and consistency to budget reporting.

Enabling factors

Key enabling factors include sufficient time, personnel, and funding to conduct a variety of trainings, workshops, and meetings at the local level. The development of easy-to-understand materials, knowledge products, and supporting activities is also an essential factor.

Lesson learned

Trainings and workshops should focus on translating complex information into clear and actionable messages. This is crucial to ensure their effectiveness and address the main challenge of legal complexity and ambiguity in the context of the NRUF. Practical components, such as hands-on activities, further support the achievement of learning outcomes by reflecting what local actors will have to do, in practice, when defining and reporting their budgets. Finally, trainings and workshops should be tailored to specific audiences. Since local governments are responsible for implementing the NRUF, and each province has unique opportunities and constraints, it is effective to provide separate trainings for individual local governments rather than solely aggregating all personal at a higher level.

Impacts

The solution effectively strengthened the biodiversity impact of local budgets through the enforcement of the NRUF. Biodiversity finance in Mongolia increased from USD 4.29 million in 2021 to USD 13.96 million in 2024, a rise of 225%. This amount almost closes the estimated biodiversity finance gap of USD 10 million per year in Mongolia. It is also more than twice the expected USD 5–6 million per year with this solution.

Revenue from fees for using natural resources grew from USD 11.37 million in 2021 to USD 83.10 million in 2024, an increase of approximately 630%.

The estimated implementation level of the NRUF via local budgets increased to 64.3% in 2024, compared with 26% in 2021.

Until September 2025, 1,944 individuals participated in in-class trainings, 1,622 in country-wide online trainings, and 2,296 in online trainings upon request of a province. Across all these trainings, 56% of the participants (or 3,311) were women. Workshops and forums had 1,444 participants, about 50% of whom were women (730). Various in-person meetings with local decision-makers involved 1,723 participants, with 44% of women (768).

Beneficiaries

Local decision-makers benefit from this solution by improving their budgeting skills and implementing the NRUF. Indirect beneficiaries include the whole population of Mongolia, which benefits from more protected ecosystems through efficient budget allocation.