Making the Case for Fish

Fish plays a crucial role in global food and nutrition security, particularly for food-insecure households. In this solution, the GIZ Global Programme Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture (GP Fish) highlights the significance of fish in combating malnutrition and promoting healthy diets. By integrating scientific research with extensive field data and practical solutions, the program offers a comprehensive overview of the current situation in various countries and suggests a way forward. Blue foods, such as fish from aquaculture, are identified as a promising source of protein and nutrients, especially in low-income and food-deficit regions. Smallholder fish production offers nutritional, economic, and environmental benefits, making it a vital component of the diets of vulnerable communities. The evidence underscores the need to boost the supply of fish in local markets. Fish from small-scale aquaculture not only addresses nutrition insecurity and poverty but also supports the sustainable transformation of food systems.

Context

Challenges addressed

Malnutrition, including undernutrition, overnutrition, and micronutrient deficiencies, is a critical aspect of food and nutrition insecurity. Inadequate intake of essential nutrients and vitamins leads to significant health concerns. One strategy to combat these deficiencies is diet diversification, particularly with animal proteins in low-income, food-deficit countries with carbohydrate-based diets. Aquatic highly nutritious blue foods, like fish and mussels, provide a solution to malnutrition. However, global fish consumption varies regionally, with the FAO predicting increasing imbalances and a decline in Africa.

Overfished wild stocks and degraded ocean ecosystems necessitate sustainable aquaculture. Yet, small-scale farmers often lack technical knowledge and financial resources for intensive production, facing high costs for formulated feeds, veterinarian products, and machinery. Intensive aquaculture also contributes to global warming, habitat destruction, and the introduction of alien species, impacting biodiversity.

Location

Process

Summary of the process

Blue Foods can play an important part in combatting food and nutrition insecurity in rural areas. But regarding the risks and negative environmental impacts of overfishing, aquaculture must be pursued sustainably to increase fish availability in local markets, especially for food-insecure populations.

The following strategy helps to provide affordable fish while ensuring producers earn a living income. This is possible through small-scale, decentralized aquaculture, adapted to the limited financial and technical capacities of smallholders. Therefore, having a significant effect on food security as well as poverty reduction in low-income countries. In contrast to vertically integrated aquaculture farms that boost economic growth, small-scale aquaculture directly increases fish consumption and incomes, allowing producers to buy other foods. GP Fish supports farming omnivorous fish like Carp and Tilapia and aims to empower producers through different trainings and practices by optimizing pond productivity and integrating fish production with agriculture. Due to requiring minimal external inputs and the sustainable use of the natural environment in this strategy, extensive and semi-intensive small-scale aquaculture has less environmental impact.

Building Blocks

The nutrition value of fish

In the first step of the solution GP Fish seeks to provide evidence about the role of fish in addressing malnutrition and supporting healthy diets, particularly for food insecure households. It is directed to professionals working in the field of food and nutrition security as well as rural development and investigates questions like “Does fish feed the poor, or is it too expensive?” By combining scientific insights with hands-on data from years of field experience, supplemented by practical examples, it aims to provide a broad overview of the current state in selected countries and a path forward.

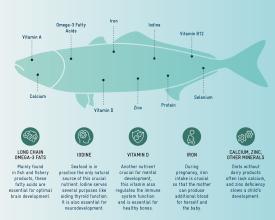

Malnutrition is the most important aspect of food and nutrition insecurity and comes in many forms: undernutrition, overnutrition, and micronutrient deficiencies, often referred to as “hidden hunger”. The latter represents a major public health concern and results from inadequate intake of nutrients, such as iron, zinc, calcium, iodine, folate, and different vitamins. Strategies to combat micronutrient deficiencies include supplementation, (agronomic) biofortification, and most importantly diet diversification, which is the focus of contemporary policy discourses concerning the improvement of human nutrition. Diversifying diets by consuming animal proteins can significantly prevent micronutrient deficiencies, especially in low-income food-deficit countries, where diets are predominantly carbohydrate-based. Fish is a highly nutritious food that provides proteins, essential fatty acids, and micronutrients, as shown in Figure 1, to the point that it is sometimes referred to as a “superfood”. Due to its nutritional properties, even small quantities of fish can make important contributions to food and nutrition security. This is particularly true for small fish species that are consumed whole – including bones, heads, and guts –in regions where nutritional deficiencies and reliance on blue foods are high.

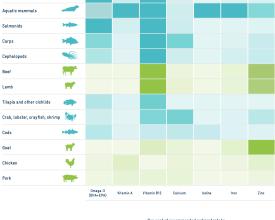

Figure 2 shows the share of recommended nutrient intake when consuming aquatic vs. terrestrial foods. Food sources are arranged from highest (top) to lowest (bottom) nutrient density. Visibly, aquatic “blue” foods like fish and mussels, are richer in nutrients compared to terrestrial sources. They are specifically good sources for Omega-3 fatty acids and Vitamin B12. Therefore, “blue foods” not only offer a remarkable opportunity for transforming our food systems but also contribute to tackling malnutrition.

Evidence: The current role of fish

Globally, fish consumption shows strong regional differences. For instance, in 2009 the average yearly fish consumption per capita in Africa was 9kg, while in Asia it reached almost 21kg per person. On every continent, small island developing states or coastal countries have higher consumption rates than their landlocked counterparts. In addition to these differences, the FAO State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture report of 2022 predicts these regional imbalances to increase in the future while fish consumption in Africa is expected to further decline.

These observations are consistent with the findings of the baseline studies conducted by the GP Fish, which found that the median annual fish consumption per capita was 0.9 kg in Malawi (2018), 1.1kg in Madagascar (2018), 1.8 kg in Zambia (2021), but 24.4kg in Cambodia (2022). It must be noted that these consumption patterns reflect the situation of the rural population, who typically have lower incomes compared to the national average. Considering the recommended average yearly fish consumption of 10 kg per person, these findings are worrying.

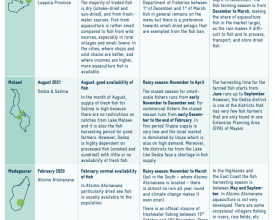

Considering the importance of fish as a protein and nutrient source for rural households it is important to better understand fish consumption patterns and their impact on food and nutrition security. In Malawi, Madagascar, Zambia and Cambodia the GP Fish and the Global Programme Food and Nutrition Security, Enhanced Resilience (GP Food and Nutrition Security hereafter) are working together to improve food and nutrition security. While the data from the GP Fish are focused on fish production and consumption of close by consumers, data from the GP Food and Nutrition Security provide information about the consumption of different protein sources by the Individual Dietary Diversity Score (IDDS). The GP Food and Nutrition Security collected data from women of reproductive age living in rural, low-income households, not focusing on people involved in the fisheries and aquaculture sector and the surveys included questions to determine a household food security status. Using the extensive dataset allowed an assessment of the current role of fish in comparison to other animal and plant protein sources, without the bias of an increased fish consumption among households involved in fish production. Given that data collection was based on 24-hour recalls, the table in the Annex contextualizes the date of the survey with seasonal implications on fish availability (fishing ban, harvesting seasons), indicating that results can be considered representative.

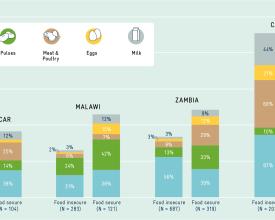

The frequency of the consumption of various protein sources over the last 24 hours, disaggregated by food security status, is shown in Figure 3. The food protein sources include fish and seafood, pulses (beans, peas, lentils), meat and poultry, eggs, and milk and dairy products. The percentages indicate how many of the respondents consumed a particular protein source (e.g., 19% of the food insecure women in Madagascar have consumed fish and seafood in the last 24 hours). The overall height of the column indicates the aggregated frequency of protein consumption by respondents for each country. Lowest frequency of protein consumption within the last 24 hours for food insecure respondents was found in Madagascar and the highest in Cambodia.

Figure 3 reveals several interesting trends:

1. In general, fish is currently the most frequently consumed protein source in nearly all countries. The importance of fish as a protein source can be explained by the fact that fish is often more affordable, more accessible, and culturally preferred compared to other animal- or plant-based protein sources.

2. Food secure respondents do not in general consume fish more frequently compared to food insecure respondents. This indicates that fish is a source of protein and nutrients that is accessible also to the most vulnerable, namely the food insecure population.

3. The results show regional differences in the frequency of protein consumption between African countries and Cambodia: in Madagascar, Malawi, and Zambia, between 19 – 56% of food insecure respondents and 38 –39% of food secure respondents have consumed fish during the last 24 hours, while in Cambodia more than 80% of the respondents consumed fish during the last 24 hours, independent of the food security status. These results are consistent with the abundance of fish in Cambodia, while access to fish in African countries is often limited by seasonality and distance from water bodies.

In addition to the differences between countries, Figure 4 illustrates high differences in consumption patterns within one country. In Zambia, the GP Food and Nutrition Security found fish to be a consumed by 68.3% (food insecure) and 88.5% (food secure) of the interviewed women in the last 24 hours, while in the Eastern Province, it was only 16.5% and 23.2% respectively. This is consistent with the results from the GP Fish survey, which found that the median annual fish consumption in Luapula Province was 2.2kg and 5.2 kg per capita, while fish consumption in Eastern Province amounts to only 0.9 kg for food insecure and 2kg per year for the food secure respondents. These results suggest that the Chambeshi/Luapula river system and connected wetlands in Luapula Province make fish more accessible than in the rather dry Eastern Province. For the success of new interventions in the field of food and nutrition security related to fish production and consumption, the local conditions and cultural context are important factors to consider during the planning process.

How to make more fish available in the local market

What strategies need to be pursued to make more fish available to consumers in local markets? Because wild fish stocks are generally overfished, and the oceans’ ecosystems experience severe degradation the logical strategy is to increase fish supply through aquaculture. When increasing fish availability, especially for the food insecure population, the approach chosen must be environmentally sustainable, provide fish at an affordable price for this group (e.g., by avoiding additional costs such as for transportation) and should still offer the opportunity for producers to earn a living income.

The approach should therefore be centered around sustainable, decentralized aquaculture adapted to the limited financial and technical capacities of smallholders. Small-scale aquaculture in low-income countries plays already a crucial role in food and nutrition security as well as poverty reduction but still has significant potential to grow. On the one hand, vertically integrated aquaculture farms (companies that expand production to up- or downstream supply-chain activities) make important contributions to a country’s economic growth by increasing export earnings, but they usually have only little impact on the local fish supply and food security. On the other hand, small-scale aquaculture directly contributes to a higher fish consumption by the producers, depending on cultural preference for fish as a source of animal protein and to higher incomes that allow producers to purchase other foods.

When evaluating aquaculture as a source of income, it is important to consider that most small-scale farmers have little technical knowledge and financial capacities. These constraints prevent them from making larger investments for infrastructure and inputs, which are required when operating an intensive aquaculture production system. Formulated feeds, veterinarian products and machinery can significantly increase aquaculture production but are in most cases financially prohibitive for smallholders in remote rural areas. The required investments exceed their financial capacities by far and credits would put the household economies at risk. For this reason, technical and financial capacity development is so important. Optimizing the productivity of earthen ponds with low investments for fertilizer and supplementary feeds generating high profits per kg fish produced seems a workable way forward.

As an example, for a technique increasing production and being adapted to smallholders’ capacities, the GP Fish has introduced intermittent harvesting of Tilapia in Malawi. This practice is applied in mixed sex cultures of Tilapia, based on natural feed supplemented with agricultural by-products. Excess Tilapias, that hatched during the production cycle, are harvested by size-selective traps before reaching reproductive age. These frequently harvested fish are an easy-accessible protein source and nutrient-rich food component for a diversified diet and surplus production is generating additional income. Intermittent harvesting also reduces the economic risk of losing the entire production due to predators, theft, diseases, or natural disasters.

Benefits of small-scale aquaculture comparing to industrial production

In addition to its economic viability, small-scale aquaculture is usually more environmentally friendly compared to industrial production systems based on industrialized feeds. Fish feed usually includes a certain ratio of fishmeal and fish oil and these ingredients are produced mainly from small pelagic fish from capture fisheries, which put an additional burden on the marine environment. It also affects the food insecure population because small pelagic fish are highly nutritious and help to combat food and nutrition insecurity directly. Fish feed also includes agricultural products like corn and soya, thus competing with food production for human consumption. Despite the negative externalities on ocean biodiversity, research has also shown that intensive aquaculture systems contribute more to global warming through automated processes and high demand for production inputs. Additionally, these systems cause habitat destruction and introduce alien species, which further affect the indigenous biodiversity. In contrast, extensive and semi-intensive small-scale aquacultures requires little external inputs and have less environmental impact. For this reason, GP Fish supports small-scale aquaculture farming of omnivorous fish species such as Carp and Tilapia. The aim is to empower producers technically and economically by optimizing pond productivity and integrating fish production into agriculture activities. This approach uses the natural environment sustainably to promote fish production.

Regular evaluations

To ensure that fish production supported by the GP Fish is an accessible protein source also for the most vulnerable, GP Fish regularly tracks fish prices and the share of total production accessible to the food insecure population. According to the conducted surveys 90 %, 58 %, 84 %, and 99 % of farmed fish is accessible for the food insecure population in Madagascar, Malawi, Zambia, and Cambodia respectively (status 2023). These numbers again highlight the potential of extensive and semi-intensive aquaculture techniques to supply affordable protein and nutrients in areas with a high share of vulnerable people.

Impacts

The project emphasizes the importance of technical and financial capacity development to optimize the productivity of earthen ponds with minimal investments in fertilizer and supplementary feeds, yielding high profits per kilogram of fish produced. Smallholder fish producers gain significant profits per kilogram of fish and produce more products for their communities.

Therefore, improving the accessibility of fish products for the food-insecure populations as well. According to the conducted surveys 90 %, 58 %, 84 %, and 99 % of farmed fish is accessible for the food insecure population in Madagascar, Malawi, Zambia, and Cambodia (status 2023). This highlights the potential of extensive and semi-intensive aquaculture to provide affordable protein and nutrients in vulnerable areas.

Furthermore, extensive, and semi-intensive small-scale aquaculture requires fewer external inputs and has a lower environmental impact. The introduction of foreign species and a high demand for production inputs can be avoided. Instead, fish production is integrated into agricultural activities.

Blue foods, such as fish from aquaculture, offer nutritional, economic, and environmental benefits, particularly in low-income and food-deficit countries. The project underscores the need to increase fish supply in local markets to combat nutrition insecurity and poverty, contributing to the sustainable transformation of food systems.

Beneficiaries

Smallholder fish producers gain economic benefits and optimize their productivity.

Better access to fish addresses nutrition insecurity and food poverty in vulnerable communities.

The approach contributes to the sustainable transformation of our food systems.

Sustainable Development Goals

Story

One of the many beneficiaries is the Mwangonde family from Mzuzu in the Northern Region of Malawi, whose inspiring story encapsulates the possibilities of our solution.

When the fish farmers Odoi and Florence Mwangonde first started their family business, they were met with skepticism from their community. But they proved them wrong when they turned their water-logged land full of horticultural crops into a fish farming site with 13 ponds stretching 3.5 hectares. To support operations, the family-run business received training on good aquaculture practices through the Aquaculture Value Chain Project (AVCP) in Malawi. The training helped Odoi and Florence to plan more efficiently, cutting unnecessary costs and making the highest possible revenue.

While the Mwangondes face a number of challenges including lack of qualified staff, scarcity of quality fish feed and slow growth rates of indigenous fish species, they focus on devising short- and long-term solutions for their fish farming business, always keeping their community in mind. To avoid pollution in the surrounding communities and to maximise land use, Odoi and Florence integrated banana plantations in their farm, using pond water for irrigation. This integration also helped them to increase revenue and profits from the farm. Currently the farm produces nine tons per year, feeding up to 10,500 people in the Mzuzu region, but the Mwangondes hope to become large fish and fingerling producers in the future, able to supply their community and beyond. With every new member, the Mwangondes’ commitment to their community only grows: “Every time we hear a baby is born in our community, we are very happy because we know that we have one more mouth to feed. We are proud to be part of a journey to provide affordable protein to our community”, says Mr. Mwangonde.