Integración de los conocimientos locales en la gestión de los parques

Los complejos alrededores del Área Protegida Nacional de Hin Nam No exigen que la unidad de gestión del AP cogestione la zona con los aldeanos locales. Para ello es necesario un entendimiento común de la zona. Los elementos básicos de la cartografía de senderos de las aldeas, el sistema de guardabosques de las aldeas, la recopilación de datos SMART, la zonificación participativa y el seguimiento científico de la biodiversidad ayudan a recopilar información, procesar los datos y crear una zonificación y una normativa para gestionar eficazmente el parque implicando a los aldeanos y aumentando la mano de obra del AP con guardabosques de las aldeas.

Contexto

Défis à relever

Ubicación

Procesar

Resumen del proceso

Bloques de construcción

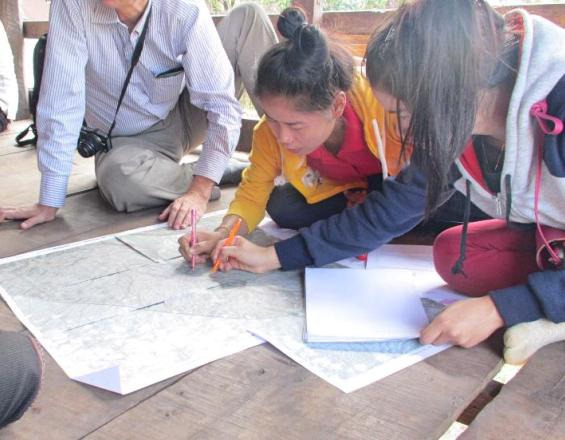

Cartografía de las rutas de los aldeanos; captación de los conocimientos locales

Factores facilitadores

Lección aprendida

Sistema de guardas forestales

Factores facilitadores

Lección aprendida

Recursos

Herramienta SMART de recogida de datos

Factores facilitadores

Lección aprendida

Zonificación participativa

Factores facilitadores

Lección aprendida

Seguimiento científico de la biodiversidad

Factores facilitadores

Lección aprendida

Impactos

1) Sentimiento de orgullo de los aldeanos y los guardas forestales porque tienen el derecho y la obligación de proteger la zona de los forasteros. Esto ha dado lugar a la apropiación de los objetivos de protección. Ahora, incluso los guardas del pueblo piden ayuda a la administración para evitar que sus propios vecinos infrinjan las leyes acordadas en común, ya que no pueden hacer cumplir la ley a las autoridades del pueblo o a sus amigos. 2) Diversificación de los ingresos de los guardabosques de las aldeas, al margen de la agricultura o la ganadería, sin que pasen a ser dependientes, lo que permite realizar patrullas rentables sin necesidad de contar con puestos de guardabosques y su mantenimiento. 3) Mejora de la gestión gracias al conocimiento de los nombres locales y a la recopilación de datos sobre observaciones de fauna y amenazas. El valor de los datos recopilados ha dado lugar a que el Jefe de la Oficina Provincial de Recursos Naturales y Medio Ambiente solicite actualizaciones periódicas de las amenazas y viajes contra la caza furtiva por parte de los departamentos combinados.

Beneficiarios

Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible

Historia