To ensure quality and safety in the fish value chain, from catch to consumer, it's vital to consider all steps of the value chain due to potential food safety risks. Implementing hygiene and quality trainings, introducing first sale certificates, and establishing control plans for state institutions are key interventions. A thorough value chain analysis is crucial for identifying improvement areas and require visits to actors and review of hygiene regulations. Based on this analysis, targeted interventions can be identified, ranging from policy to practical actions, involving research enhancement, regulatory support, and capacity development.

The direct actors in the value chain are fishermen, retailers, traders, transporters, warehouse workers and suppliers who are involved in the production, processing, delivery or sale of a product to the consumer. They are the first point of contact when it comes to offering the consumer a safe product of high quality. Accordingly, they represent the target group that needs to be informed about the hygienic handling of products and the aspects of production, storage and transportation deteriorating quality. The implementation of a training plan can strengthen knowledge about hygiene, quality and control practices for the various steps of the value chain.

With so many different actors, there are certain topics that are only important to some while other topics are clearly important for everyone: raising awareness of biochemical processes such as microbes, knowledge about food-borne infections and diseases, maintaining personal hygiene at the workplace, recognizing fresh and spoilt products, using ice to uphold the cold chain or cleaning and disinfecting the workplace and equipment. However, while fishermen, are primarily concerned with the accurate storage and immediate cooling to prevent the deterioration of their catch, processors focus more on the hygienic handling of the processing equipment. Accordingly, it is essential to adapt learning content and teaching methods to the different actors along the value chain, like demonstrations of storage and cooling systems on the fishing boats, or on-the-job trainings concerning proper handling of processing equipment.

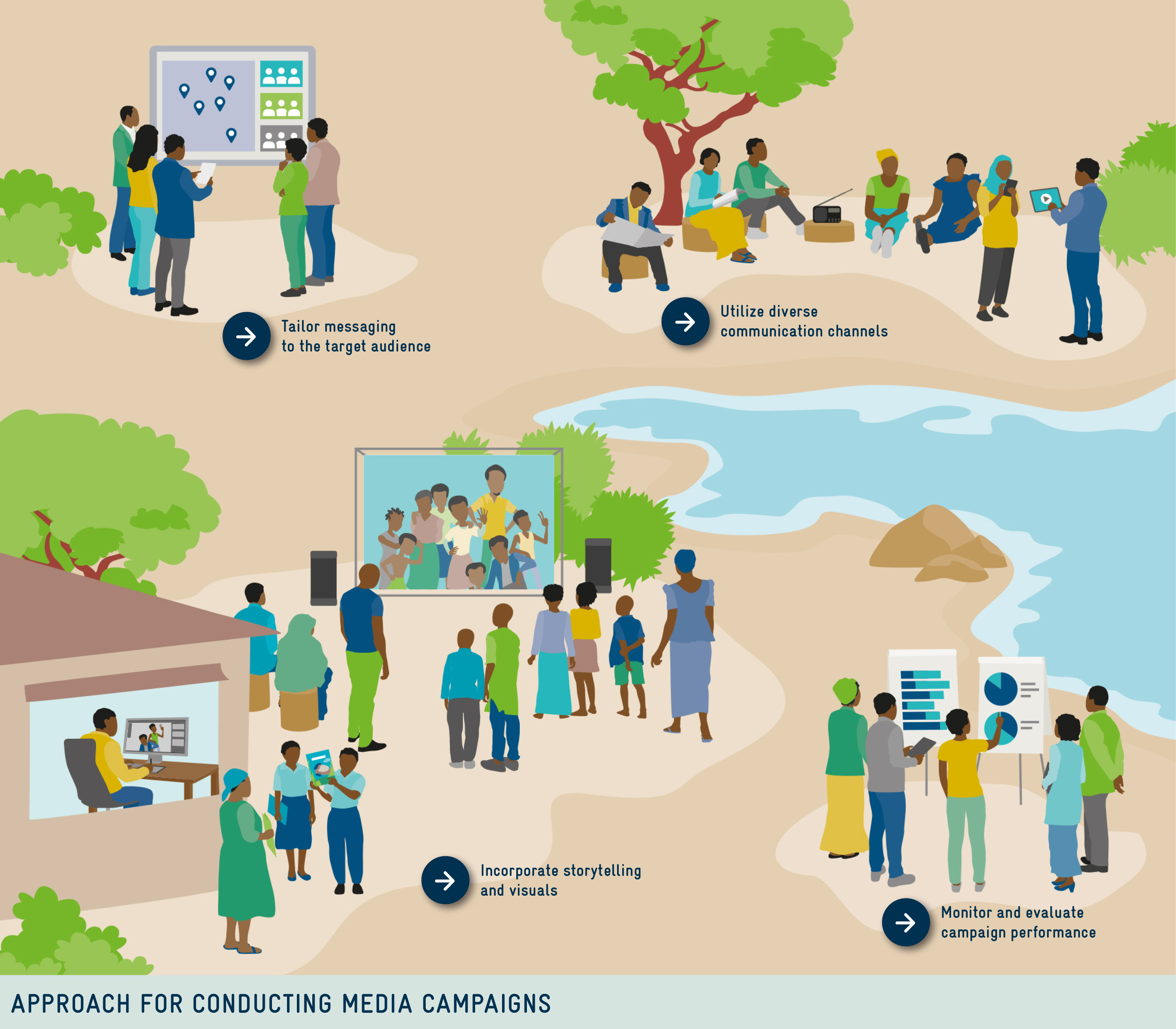

Furthermore, didactics must be developed that take into account the experience of fisheries and aquaculture experts. In the context of high illiteracy diagrams, drawings and photographs can be used. Also, the language must be adapted to the target group. In addition, training content can be gathered and summarized in small booklets e.g. guidelines that provide the actors with a long-term option to revise training contents. Here, as with the training content, it is advantageous to adapt the guidelines to the different actors in the value chain, e.g. one guide for fishing, another for processing and so on. By doing this, value chain actors can be addressed directly and do not loose their learning ambition by going through learning content that does not fully affect their work. Finally, the dissemination of the guidelines should be adapted to the local context; not every country has the same media capacities but in addition to handing out printed versions, apps proofed to be a way to spread training contents easily.

To ensure that the theoretical hygiene and quality trainings become actual practice, it's essential to discuss and confirm understanding with trainees. Using short feedback forms and coaching loops post-training help verify and further improve learning and communication effectiveness. Additionally, evaluating knowledge application, such as willingness to invest in ice for fish storage, is key. Highlighting the long-term benefits, like quality improvement and potential for higher prices, despite initial costs, is crucial for convincing participants of the value.

In addition to understanding, the implementation of training content must also be taken into account. It is important to find out at an early stage which hygiene practices are feasible in the local context. If the purchase price of ice does not justify the additional benefit of fresh quality, no trainee will adhere to the training content. To stay with the example of ice, the question also arises as to whether the necessary infrastructure is in place: are there ice producers, operational cold chains and the necessary equipment? Next to the spread of misinformation, the greatest danger in communicating training content lies in conveying messages that simply cannot be implemented by the local trainees, as they do not have the means to do so or the supporting infrastructure is just too unstable.

Next to the post-training feedback the effectiveness of the training can be assessed through a second follow-up survey, reflecting on key elements of its content. The timing between these evaluations varies with the topic; for instance, 3-6 months may be sufficient to review acceptance to personal hygiene practices, such as handwashing at work. However, evaluating changes like the use of ice for fish storage on boats might require up to a year, accounting for off-seasons and fishing periods. Even if evaluations are time-consuming, they are crucial to revise, adapt and further develop training materials to meet the needs of the participants.

In terms of the capacity development approach, a training-of-trainers strategy can be implemented in the training plan. Training local knowledge brokers like chairmen of fishing or trading associations or market supervisors in the field of hygiene and quality can have a lasting effect in anchoring this knowledge within partnering institutions and in generating spill-over effects through word of mouth at regional level. Sensitising consumers and buyers are also crucial, to understand the importance of fresh fish. Hardly anyone will take on additional work and costs to create a quality product that is not demanded.