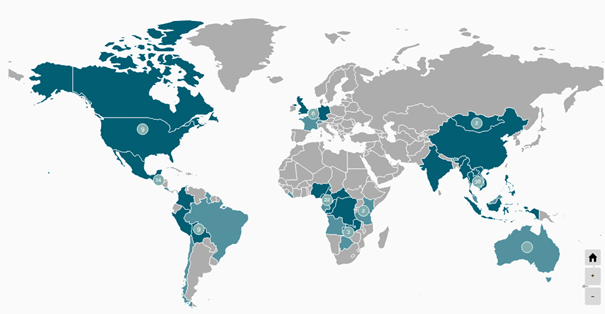

While APOPO is the leading organisation in training scent detection rats, we rely on our partners for a wide range of support. Without them, deploying scent detection rats would not be possible. Such partners range from local partners such as the Sokoine University of Agriculture, to international partners such as Mine Action Authorities, governments, donors, and specialised organisations.

For example, the wildlife detection project partners with the Endangered Wildlife Trust of South Africa. The project has been funded by a wide range of government donors such as

- The German Government (through the GIZ 'Partnership against Wildlife Crime in Africa and Asia' Global Program)

- The UNDP-GEF-USAID 'Reducing Maritime Trafficking of Wildlife between Africa and Asia' Project

- The UK 'Illegal Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund'

- The Wildlife Conservation Network

- The Pangolin Crisis Fund

- US Fish and Wildlife

We rely heavily on support from the Tanzanian Wildlife Management Authority (TAWA) for provision of training aids, and, recently, the support from the Dar es Salaam Joint Port Control Unit in order to conduct operational trials for illegal wildlife detection.

Trust, collaboration, networking, knowledge exchange, integrity, supporting evidence, reporting, media and outreach.

Building relationships takes time and trust. Open and honest dissemination of results, goals, and setbacks ensures that partners feel that they can trust your organisation. In addition, when dealing with governments and partners in countries other than your 'own', we have found it helpful to have a person who is familiar with the way the specific countries' governments work. An in-depth understanding of cultural values and customs can greatly enhance partnerships. In addition, expectations should be clearly communicated across all parties to avoid frustration and misunderstandings.