This building block emphasises community participation in monitoring, utilising citizen science and accessible data platforms to ensure local knowledge informs adaptive management and contributes to the long-term success of mangrove restoration.

Effective monitoring and evaluation is necessary for adaptive management and long-term success in mangrove restoration. In implementing CBEMR, Wetlands International developed a restoration plan with clearly defined goals and objectives aligned with measurable and relevant indicators.

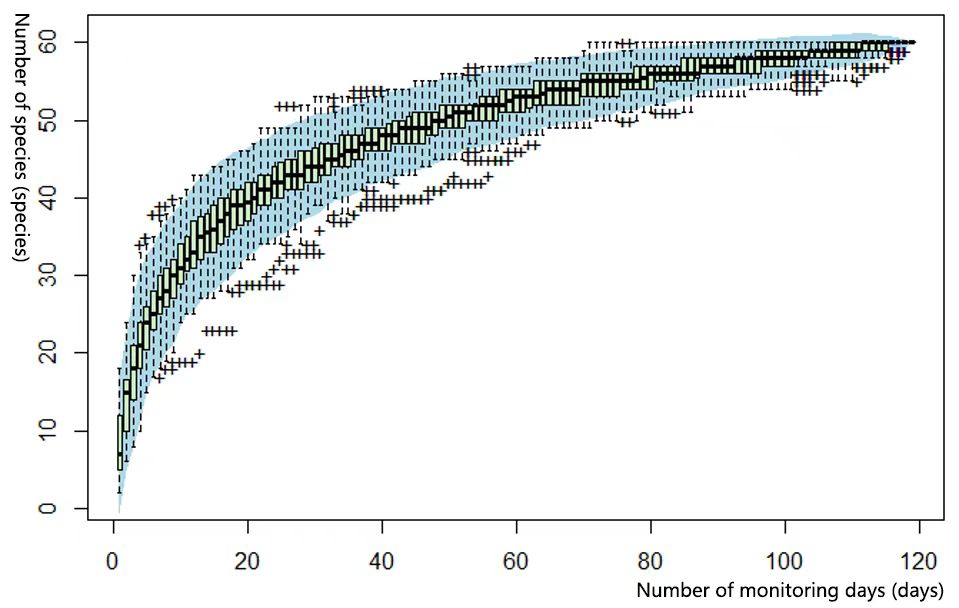

To ensure accurate and consistent data collection, a variety of methods were employed, including surveys, field observations, remote sensing, and the use of the Mangrove Restoration Tracker Tool. This tool, integrated with the Global Mangrove Watch platform, provided a standardised framework for documenting and tracking restoration progress, facilitating learning and information exchange among practitioners.

Strengthening the capacities of mangrove champions from Lamu and Tana counties through standardised CBEMR trainings and tools provided for the integration of citizen science initiatives in mangrove restoration monitoring.

Creating platforms for community feedback and input such as the national and sub-national mangrove management committees ensures that local knowledge and perspectives are incorporated into adaptive management strategies. By using monitoring data to inform decision-making and adapt project strategies, restoration efforts such as those in Kitangani and Pate restoration sites have been continuously improved to maximise effectiveness and achieve long-term success.