This building block captures the iterative process of translating user insights into tangible menstrual pad prototypes. Guided by the national field research (Building Block 1), Sparśa developed and tested multiple pad designs to balance absorbency, retention, comfort, hygiene, and compostability.

The process took place in two phases:

Phase 1 – Manual prototyping (pre-factory):

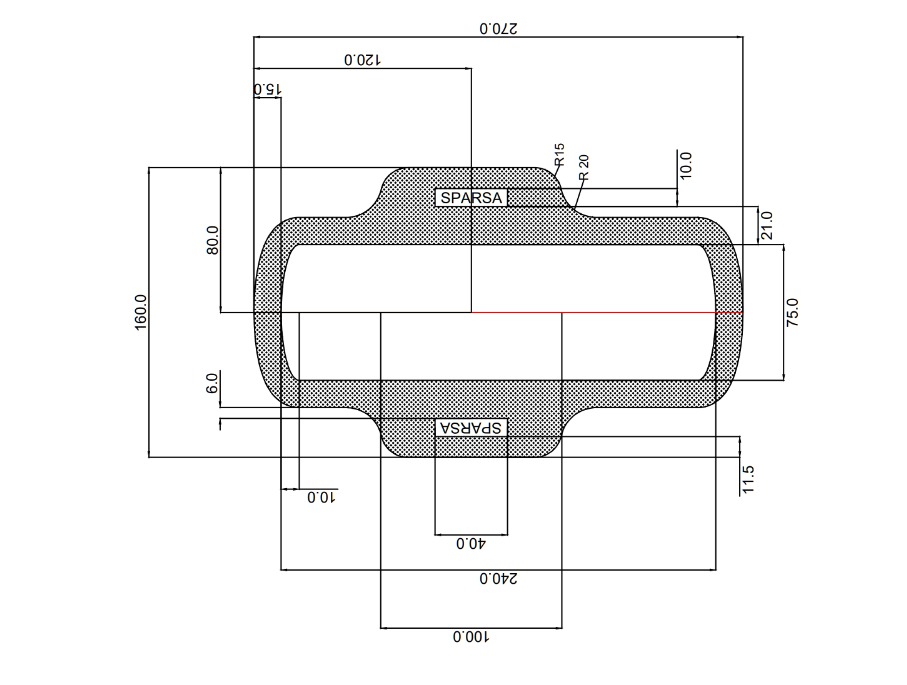

Before the factory was operational, pads were manually assembled to explore different material combinations and layering systems. Prototypes tested 3–5 layers, usually including a soft top sheet, transfer layer, absorbent core, biobased SAP (super absorbent polymer), and a compostable back sheet. Materials such as non-woven viscose, non-woven cotton, banana fibre, CMC (carboxymethyl cellulose), guar gum, sodium alginate, banana paper, biodegradable films, and glue were evaluated.

Key findings showed that while achieving high total absorbency was relatively easy — Sparśa pads even outperformed some conventional pads in total immersion tests — the main challenge lay in retention under pressure. Conventional pads use plastic hydrophobic topsheets that allow one-way fluid flow. Compostable alternatives like viscose or cotton are hydrophilic, risking surface wetness. Prototyping revealed the need to accelerate liquid transfer into the core to keep the top layer comfortable and dry.

Phase 2 – Machine-based prototyping (factory):

Once machinery was installed, a new round of prototyping began. Manual results provided guidance but could not be replicated exactly, as machine-made pads follow different assembly processes. Techniques such as embossing, ultrasonic sealing, and precise glue application were tested, alongside strict bioburden control protocols in the fibre factory.

Machine-made prototypes were systematically tested for absorption, retention, and bacterial counts. Internal testing protocols were developed in-house and then verified through certified laboratories. Initial results showed that bacterial loads varied significantly depending on fibre processing steps (e.g. cooking or beating order), underlining the importance of strict hygiene control.

Iterative design cycles combined laboratory testing with user comfort feedback, allowing continuous adjustments. By gradually refining layer combinations, thickness, and bonding methods, Sparśa optimized the balance between performance, hygiene, and environmental sustainability.

Annexes include PDFs with detailed prototype designs, retention test data, and bacterial count results. These resources are provided for practitioners who wish to replicate or adapt the methodology.